Urban Renewal

An economic development tool, urban renewal was used by local governments across the country including the City of Buffalo. It was a method that was meant to economically revitalize areas through public investments that stimulated private development. What it actually translated to was the wholesale destruction of what were deemed blighted areas or slums, almost entirely based on racial composition. In their places often went new highways extending to the racially-restricted suburbs.[1]

City officials expected the removal of blighted areas would increase tax revenue for the City, revitalizing decay in the urban core, and improving living conditions for the poorest slum dwellers.[2] However, urban segregation is an ongoing social war in which the state meddles in the name of “progress,” “beautification,” and even “social justice for the poor” but ends up redrawing spatial boundaries to the advantage of landowners, foreign investors, elite homeowners, and middle-class commuters.[3] Overcrowded, unsanitary, dilapidated districts would be replaced by clean, modern housing projects and civic institutions. There are four urban renewal projects that impacted the Fruit Belt, three of which affected the neighborhood indirectly.

Ellicott District & the Kensington Expressway

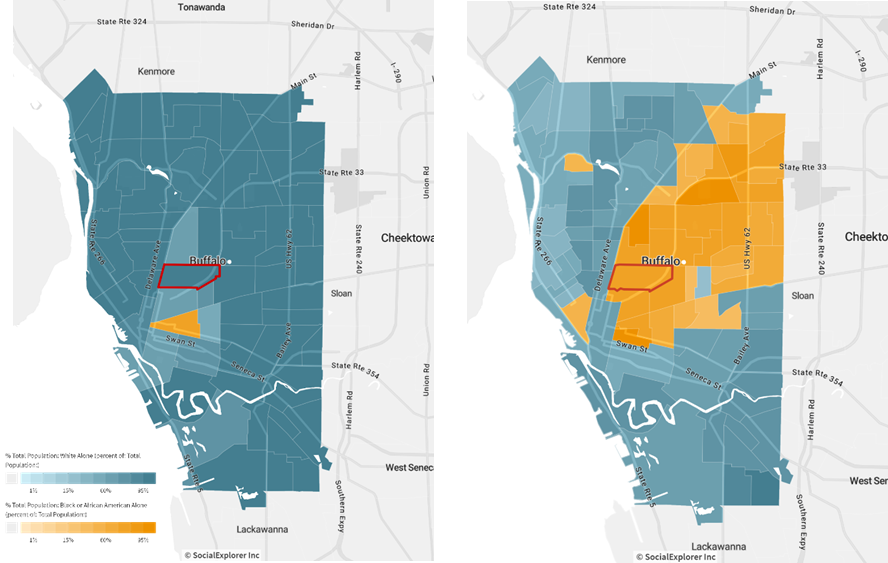

The Ellicott District was located in an area south of the Fruit Belt. In figure 3 the Fruit Belt is still census tract 31 and the Ellicott District is tract 24. It is clear from this map that as early as the 1930s the district was densely populated and segregated from the rest of the city.

Figure 3: 1930s African American Population Density Map

The combination of limited capital, slumlords, and a still growing population meant that by the 1950s the neighborhood was one of the most densely populated and impoverished in the city. Citing the prevalence of substandard and unsanitary housing, overcrowding, and inadequate public utilities, the city’s planning commission decided to demolish significant portions of the Ellicott District. In 1951, the City Planning Commission published their General Plan for the City of Buffalo, which laid out how urban decay would be combated.[4] What would go in its place was meant to be a medium density residential neighborhood, public buildings, and public green spaces.[5]

The project displaced African American households and, just a few blocks north of the neighborhood, the Fruit Belt was one of the places they resettled. As previously stated, this sudden influx of African Americans accelerated the already creeping exodus of Germans. Though many of the German families moved away, many homeowners retained their properties choosing to rent them out to incoming African Americans. This too led to social and housing issues, however, as many of the new, absentee landlords practiced price gouging and rented their small properties to multiple families.

Then, in 1954, the City announced its plan to build the Kensington Expressway, a massive, expensive highway that would help people reach downtown Buffalo faster making the city more car friendly in the process. The Kensington Expressway replaced a major portion of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Humboldt Parkway and because the expressway was built below grade it cut a trench between the Fruit Belt and the rest of the East Side.[6]

A proposal for the expressway states, “If this project is to be an asset to the city and surrounding area, it must be designed in a manner that will increase the real values of the immediate neighborhood, as well as serve the through traffic purpose for which it is proposed.”[7] This proposal also calls for green spaces along the expressway, an attempt in keeping with the parkway aesthetic. What Buffalo got, however, was not an asset but a concrete chasm that decreased property values and threw the surrounding communities into turmoil. Hundreds of buildings were torn down to make way for the expressway and many of those displaced sought refuge in the nearby Fruit Belt.

North Oak & the Medical Campus

Another major project that affected the Fruit Belt was the 1970 Oak Street Renewal Program. Located just west of the Fruit Belt, the project was meant to clear the land and expand Buffalo General Hospital and Roswell Park.[8] The program created many of the same problems the Ellicott District effort did 12 years earlier. Proponents of the project admitted that there would only be enough public housing for some of the displaced families, leaving over 300 others homeless.[9]

Figure 4: North Oak Street Mid-Demolition (1973)

The renewal objectives included “the elimination of blighting influences” and the prevention of blight recurring in the future while improving the cleared land. There is no real mention of the businesses, schools, and churches that the program would be displacing let alone the people. In fact, it is said that some residents were displaced by demolitions before the relocation study was completed and the renewal project approved so they were ineligible for federal grants and assistance to find new housing.[10]

The looming issue for the Fruit Belt because of this is gentrification. The vacant lots are being filled, with renewed demand as the Medical Campus grows, by new housing. Rod Watson, columnist for The Buffalo News, described the situation well, “The fear is that while new residents are welcome, they will come at the expense of existing ones. Those stakeholders will be priced out as speculators, developers – and the politicians they buy – drive up prices near the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus”.[11] Residents are afraid of being displaced yet again.

The increasing workforce at the Medical Campus caused a spillover of parking from its lots onto the streets of the Fruit Belt. Many residents complained that they would not find parking on their own streets let alone in front of their own homes. Initially, this spurred a call to ban outsider parking all together but the Civil Service Employees Association (CSEA) felt slighted. There was another plan issued that elicited a compromise: half of the parking spaces in the neighborhood would be set aside specifically for Fruit Belt resident only while the other half would be open to whomever.[12]

Masten Park

Destruction of the Ellicott District, construction of the Kensington Expressway, and demolitions caused by the Oak Street Renewal Program played the largest role in shaping the Fruit Belt but the neighborhood was also part of the Masten Park Renewal Plan.[13] In 1958, the City’s Board of Redevelopment began efforts to rehabilitate the Fruit Belt through the Masten Park Renewal plan. They sent inspectors house-to-house to search for housing violations and hoped that, by enforcing them, it would slow or avoid the decay that appeared to affect other neighborhoods like the Ellicott District.[14]

Demolition as Urban Policy

Some of the most visible components of decline are vacant and abandoned properties and real property disinvestment. These contribute not only to the perceptions of urban blight but to local government fiscal crises.[15] Conditions of disinvestment are more visible and widespread in some cities than in others. In the Rust Belt, spaces are often shells of their former selves with many of the structures missing, victims of scrapping, arson, and demolition.[16] Vacancy and abandonment have been a familiar sight in all of Buffalo but especially on the city’s East Side. The Fruit Belt was hit quite hard by these issues as the in-migration of African Americans never reached the numbers of the whites that were leaving, as evident in Table 1. The already aged housing stock was left empty to further decay.

While demolition is a necessary tool in many Rust Belt cities, when rolled out in standalone form it is not an effective strategy to manage vacancy. This is because the usually “built-in” demand for developable land that tends to exist in growing cities is generally lacking in cities that have or are experiencing decline.[17] The City demolished houses in the Fruit Belt throughout the 1960s to 1980s, leaving the neighborhood a husk of its former self, and there was no demand for the newly vacant land to be redeveloped.

5-In-5 Program

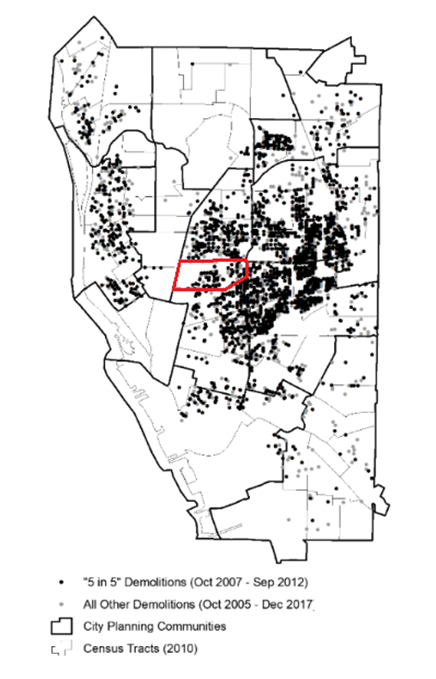

Cities across the Rust Belt have used a variety of federal and state funding to demolish as much blight as they could. Vacancy and abandonment are significant obstacles to stabilization, reinvestment, and revitalization at both the neighborhood and city level. The logic of demolishing these buildings is that if a city can remove what is being used for criminal activity or targets of arson, or that are otherwise draining the value of surrounding properties, investors will return to the neighborhoods.[18] In the City of Buffalo, the “5-in-5” program aimed to demolish 5,000 vacant and abandoned properties over five years starting in 2007.[19]

Figure 5: Distribution of all public demolitions from October 2005 to December 2017

Figure 6: Fruit Belt & North Oak Neighborhoods: Aerial Photo 1951 v. Satellite Image 2022

Figure 5 shows that the Fruit Belt (outlined) was affected by the 5-in-5 demolition program. In figure 6 , the Kensington Expressway construction and North Oak’s disappearance aside, holes in the built environment left by waves of demolition have become obvious. There are now numerous empty lots in a neighborhood that used to be fully built out.

The history of the Fruit Belt is often told in two separate pieces. There are the German immigrants whose story is full of hope and optimism and there are the African Americans whose story is one of displacement and decline. The African American story has long gone ignored due to shame over years of systemic and systematic racism. The Fruit Belt, no longer orchard filled, has watched its neighbors change drastically. The construction of the Kensington Expressway cut it off from adjoining neighborhoods. HOLC maps colored it orange and ensured its discrimination. White Flight and continued population decrease left buildings empty to rot. Urban renewal projects like the demolition of North Oak have had far reaching consequences.

Today, the threat of gentrification looms over the Fruit Belt. Parking is at a premium despite its abundance of houseless lots. There is renewed demand for vacant properties throughout the neighborhood due to the growth of the adjacent Medical Campus but what will fill them? The current residents are being threatened with displacement yet again but they are not helpless. Inhabitants have created the Fruit Belt Community Land Trust. Community Land Trusts (CLTs) are nonprofit organizations governed by a board of residents and public representatives that aim to provide lasting assets and opportunities for households and the community. They acquire vacant land and structures to develop housing, gardens, and commercial space selling homes for a low cost that remain permanently affordable.[20]

[1] “Segregated by Design,” accessed October, 2022, https://www.segregationbydesign.com/buffalo/freeways.

[2] Thomas J. Sugrue, The origins of the urban crisis : race and inequality in postwar Detroit, First Princeton classics edition. ed., Princeton studies in American politics: historical, international, and comparative perspectives, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014).

[3] Mike Davis, Planet of slums, Paperback ed. (London ; New York: Verso, 2007).

[4] City of Buffalo Redevelopment Project for the Ellicott District Redevelopment Project, (Buffalo City of Buffalo 1957).

[5] Intensive Level Survey Of The Fruit Belt, Buffalo, New York.

[6] Intensive Level Survey Of The Fruit Belt, Buffalo, New York.

[7] Kensington Expressway Arterial Improvement, Downtown Buffalo to Airport : via Cherry Street, Humboldt Parkway, Kensington Avenue, Maryvale Drive, Buffalo, New York, (Buffalo 1953).

[8] Intensive Level Survey Of The Fruit Belt, Buffalo, New York.

[9] “U.S. Awaits Bid for Aid on Renewal,” Buffalo Courier-Express, August 17 1965.

[10] Angela Keppel, “North Oak: Urban Renewal and the Lost Neighborhood of the Medical Campus,” Discovering Buffalo, One Street at a Time, 2021.

[11] Rod Watson, ” Gentrifying of Fruit Belt Tastes Sour,” The Buffalo News 2015; Watson, ” Gentrifying of Fruit Belt Tastes Sour.”

[12] Avery Schnieder, “City, state and union leaders announce agreement on Fruit Belt neighborhood parking,” (https://www.wbfo.org/local/2016-05-14/city-state-and-union-leaders-announce-agreement-on-fruit-belt-neighborhood-parking 2016).

[13] Intensive Level Survey Of The Fruit Belt, Buffalo, New York.

[14] Intensive Level Survey Of The Fruit Belt, Buffalo, New York.

[15] Weaver, Shrinking cities : understanding urban decline in the United States.

[16] Hackworth, Manufacturing decline : how racism and the conservative movement crush the American Rust Belt.

[17] Russell Weaver, “Can Shrinking Cities Demolish Vacancy? An Empirical Evaluation of a Demolition-First Approach to Vacancy Management in Buffalo, NY, USA.,” Urban Science (2018).

[18] Hackworth, Manufacturing decline : how racism and the conservative movement crush the American Rust Belt.

[19] Weaver, “Can Shrinking Cities Demolish Vacancy? An Empirical Evaluation of a Demolition-First Approach to Vacancy Management in Buffalo, NY, USA..”

[20] “What is a Community Land Trust?,” Fruit Belt Community Land Trust 2022.